“The only noise it was known to utter” - The Great Auk and the Extinction of Voice

Jon Roberts, September 2022

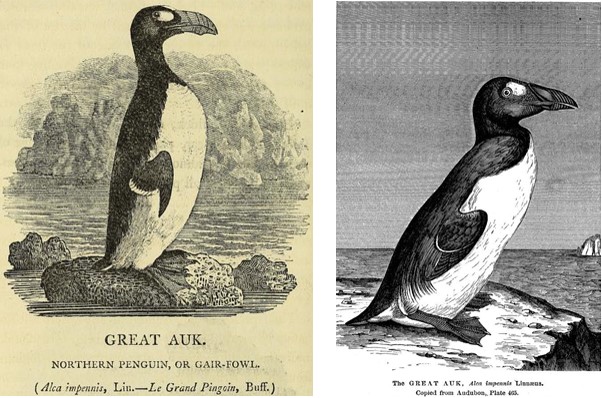

The Great Auk (Alca impennis; the Northern Penguin, Wobble, Apponatz and Garefowl) once lived across the North Atlantic, including the northern British Isles. Flightless and enormous (around 3 feet tall), it was a coastal species, feeding on fish at sea, and nesting on rocky cliff-shores. This made it useful to sailors as a reliable indicator that a ship was nearing land; but also as a source of food and feathers. In addition, ‘the Greenlanders’, claimed Thomas Pennant in 1792, ‘use the gullet as a bladder to make their darts [harpoons] buoyant in the water after they have flung them at any object of the chace’; he also asserts that the Inuit of Newfoundland ‘cloath themselves in the skins of these birds’.

These unique birds, compared by western authors with ‘the amphibious monsters of the deep’, had a variety of significances to the peoples of the North Atlantic, providing, like the sea itself, these disparate societies with a shared source of food, raiment and stories. James Orton, writing in 1869, long after the bird itself had been confined to extinction in 1844 (when the last known pair were killed) retells a tale about an auk outswimming a six-oared boat. This was not enough to save the poor bird, which, we are told, ‘was finally shot…and is now in the British Museum’.[1]

All that now remains of the great auk are remains in various museums; stories and descriptions in books; and a handful of illustrations. What does not remain is any real record of its voice. ‘The only noise it was known to utter’, writes Orton, ‘was a gurgling sound’.

While not all birds are vocal, the voices of many species form an important means of communication with their own kind as well a way for birdwatchers to identify them and enjoy their presence. Certainly the extant auks – razorbills, guillemots, puffins and the rest – can be vocal, uttering a range of calls and whistles. We can now never know for sure whether the great auk was any different.

Extinction marks the end of a species’ time on earth, the end of its opportunities to live, change and evolve as other species do. But it also marks the end of human opportunity to directly experience that species. We cannot watch or listen to the great auk anymore. Orton writes that gurgling was ‘the only noise it was known to utter’; but previous generations have robbed us of the chance to know any different. Our knowledge of the auk’s sound is frozen in time; we cannot know any more, or any better, than Orton.

We can view the great auk’s stuffed remains – but to do so is to bow not only to the hegemony of the eyes and the gaze, but also the colonial-capitalist way of experiencing through capturing, containing and possessing. The great auk is now locked away and frozen in time, deprived of the chance to vocalise, literally contained within the bounds 19th-century naturalists have built for it. And this too is the mode of possessive experiencing which has done so much to drive so many species to extinction, and has despoiled colonised societies of their treasures so that these ‘artefacts’ may be gazed at in metropolitan museums.

To experience a species in the wild – to listen to its voice and to engage with its mode of being without any intention of taking possession of it – offers a different way of experiencing nature, and one that can only be monetised by scarcity. For the experience of wildlife to be commodified, it must be confined and it must be controlled – and it must be rare. If everyone can listen to the song of a bird within five minutes’ travel of their home, then it becomes an experience which cannot be sold or possessed exclusively. Even ecotourism is premised on the scarcity of nature – it stems from the desire to see what cannot be seen elsewhere. But a song which everyone can hear cannot be possessed, and neither can the soundscape of a place, or a habitat. The sounds of a place are public by nature; they cannot be captured or walled in. To listen to the birds, to enjoy the improvised and ever-changing soundscape formed by the unconscious collaboration of countless species is an anticapitalist act which refuses the colonial urge to contain and freeze specimens in time.

But the extinction of the great auk leaves a gap in the soundscape of the North Atlantic coastlines, an uncanny silence. The voice of the great auk has been taken from places where it could once be heard; an absence of a sound testifies to the absence of a bird. The auk’s beak sits still in glass museum cases, and its voice cannot return to the cliffs which once sheltered it, or the coastlines which one nurtured it. The soundscape of the sea cliffs is ever-changing, but it has been restricted by the extinction of the great auk, avenues of possibility walled off, options of evolution denied.

Sixty years on from Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, the coastlines of the North Atlantic are still losing their soundscapes, falling quiet as populations of even once-ubiquitous gulls and seabirds crash. Which raises the question – what is the sound of extinction? Is it the lost gurgling of the great auk? The lonely crashing of the waves upon the shore, the answering silence of absent birds? Or is it the roar of the private jet ferrying callous businessmen and procrastinating politicians over a dying ocean?

The Great Auk, from T. Bewick, History of British Birds (L, 1804) and J. Orton, ‘The Great Auk’, The American Naturalist 3 (R, 1869).

Bibliography

Bewick, T., History of British Birds Vol. 2 (Newcastle, 1804) https://archive.org/details/historyofbritish21804bewi/page/162/mode/2up

Hardy, F.P., ‘Testimony of Some Early Voyagers on the Great Auk’ (1888), https://archive.org/details/biostor-121261/mode/2up

Orton, J. ‘The Great Auk’, The American Naturalist 3 (1869) https://archive.org/details/jstor-2447555/page/n1/mode/2up

Pearson, G.T., Birds of America, (New York, 1923) https://archive.org/details/birdsofamerica01pear/page/30/mode/2up

Pennant, T., Arctic Zoology (London, 1792), https://archive.org/details/McGillLibrary-rbsc_blackerwood_artic-zoology_folioQL105P4_v2-20310/page/n265/mode/2up

[1] This particular specimen can no longer be found in the British Museum’s catalogue, but a 1702 spoon made by the Northeast Peoples from great auk bone can be: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/E_Am-SLMisc-1730